Stories

“Hey, Doctor J…” by Joe Parkin July 08 2019

Former professional cyclist and published author Joe Parkin recounts his quest for the perfect cycling shoe in the new era of clipless pedals and his magical form during the 1988 season…

I’m a child of the ‘70s. I was baptized by bad fashion, zero point zero technology, three television stations that broadcasted 30-minute sitcoms, sports, the odd Movie of the Week and straight-up, no-nonsense news.

On the weekends, if I was lucky, ABC’s Wide World of Sports would bring me something beyond baseball, football and basketball — sports that inspired my imagination a bit more than the big American three — though I watched those, too.

Between the action, of course, there were commercials. I have no idea whether it was the nature of my developing brain or the quality of the work that allows [read: forces] me to remember the ad jingles for so many products, so many years after I first heard them. I can sing you the Chicken of the Sea Tuna ad, the Apple Jacks Cereal ad, Alka Seltzer, various Coca-Cola campaigns, Hamm’s Beer and a whole gaggle of others.

There’s only one sporting-goods product spot that ever got my attention in those days, and that was the Hey, Doctor J, where’d you get those moves? ad that Converse produced in 1977. If you can get past the short-shorts fashion of ‘70s hoops, the low-tech nature of his sneakers is shocking. And I lived back then, experienced it.

Eight years after those Julius Erving Converse ads aired, Bernard Hinault claimed his fifth and final Tour de France victory. Aside from that win being a record tying number five with Merckx and Anquetil (at the time), it was the first time that a rider won the Tour de France using clipless pedals.

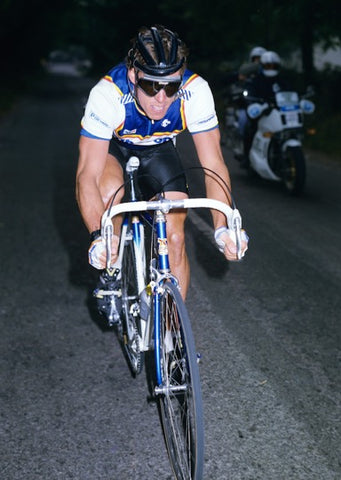

To put things into perspective: I started dabbling in road-bike racing in 1984. In 1986, I went to Belgium to be serious about it. In 1987, I turned professional. Stephan Roche was the last rider to win the Tour de France using toe-clips and straps in 1987. In 1988, I rode clipless pedals (Mavic’s Look version) for the very first time. Sean Kelly, the last of the holdouts, switched to clipless in 1993.

For anyone born after Hinault won that ’85 Tour on Look pedals, the idea of racing with a leather strap cinched tight across the top of your foot — sometimes rendering it numb in the process — must seem like the worst idea ever. Given modern shoe design, a toe-strap is kind of the worst idea ever. But, in the mid 80s, we weren’t dealing with cycling shoes designed for clipless pedals. Nope, we were mostly using shoes designed to be slipped into a metal cage and secured with a leather strap, so they really didn’t need much structure. And clipless pedals weren’t really a big thing yet.

The best clip-and-strap shoe I ever rode was Sidi’s Cycle Titanium. Basically, it was a black leather ballet slipper with a built-in cleat system — which meant you didn’t have to manually tack the cleat into place. The sole was leather and flexi, but the size of a standard pedal more than compensated for the soft sole.

But in 1988, when I knew I would be clicking in, I went searching for a personal shoe sponsor. Andy Hampsten had been wearing Lake shoes and, based on the way he climbed in them, I figured they could be the shoes for me. I wanted to climb like Andy did. Who didn’t? I contacted Lake, and they agreed to set me up with a few pairs.

The Lakes had a fair amount of curve in the sole, similar to Adidas’ cycling shoes, and the mounting setup in those early models was pretty far forward, which meant —for me at least — that I couldn’t get the foot position I wanted on the pedal. Add to that the fact that we didn’t understand back then that this new Look design placed your foot farther above the pedal’s axle, meaning you had a lower effective saddle position.

This was my first full year as a pro, mind you, first time racing the Spring Classics, and I was torturing the hell out of my knees. Days off the bike, physical therapy and painful cortisone injections — directly in the troubled tendon areas — marked at least half of my early season.

I started trying out other shoes. I’ve joked that I might be the Imelda Marcos of cycling shoes, but it’s probably not far from the truth. Along with trying different brands, I was also experimenting with shoes that were up to three sizes too small — and by that I mean too small by racing shoe standards. Pain and black toenails were a way of life. And I still couldn’t find my perfect shoe solution.

I was pedaling home one day from a training ride, and I stopped at my local bike shop — which doubled as a barbershop. They didn’t carry a ton of stuff, because they simply didn’t have room for it, and usually they’d have to special order things for me. But they did have a fresh shipment of Brancale cycling shoes, the, Dynamic, the kind Greg LeMond was riding. I tried them. They fit. One more pair of shoes? Why not?

Brancale Shoes Through The Years: 1982, 1986, Present

Now, there were certainly other shoes being developed at the time, but these were the first I ever rode that provided the structure and support needed for clipless pedals. The toe box was ample, the heel counter was solid and the curve of the sole was perfect for my cleat placement and pedaling style.

My new shoes and I got along famously right from the get-go. My knees felt good and I started riding well. And my results kept getting better as the season progressed.

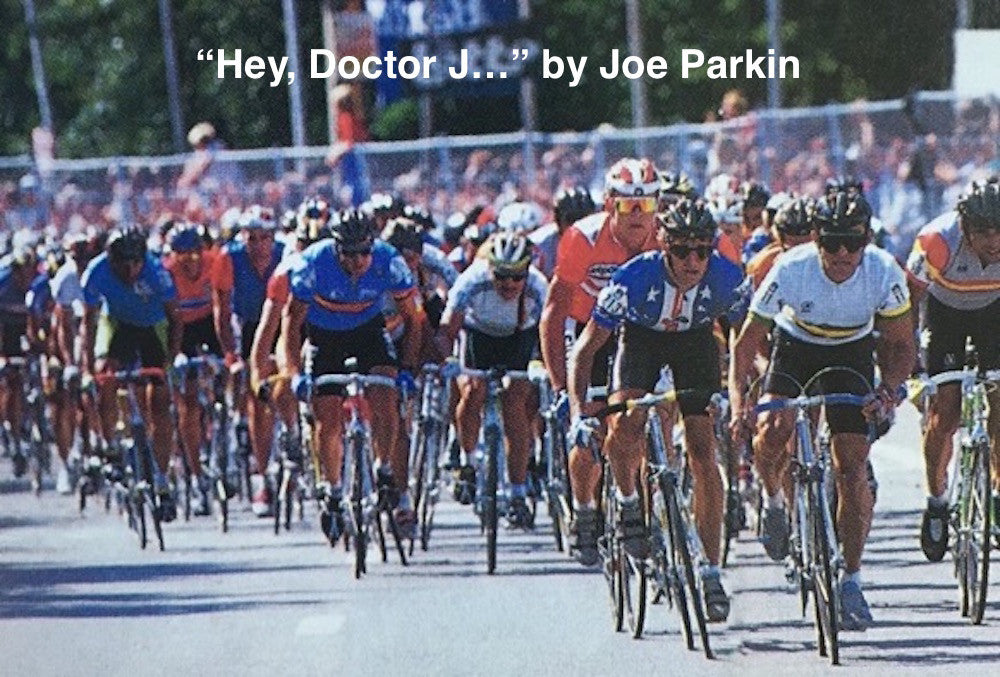

By late summer, the magical ‘form’ started to happen. I had a pretty decent Vuelta Ciclista a Burgos, and managed to attract the attention of one of the biggest teams in the peloton. I rode to a top-10 in the Tour of Belgium.

And then came the World Championships in Ronse, Belgium. Luck was not on my side that day, as a flat front tire at the worst possible moment sent me packing. But who really knows what would have happened if nothing mechanical would’ve happened.

But man, I felt great that day. Legs were good, head was good, I never felt my feet, and I felt like I could do anything. If you’ve been lucky enough to have one of those days on a bike, you know that sometimes, that is enough.

That was almost 30 years ago. I never found that perfect feeling again, but at least I had it once.

Hey Doctor J, where’d you get those moves?

I actually do believe in magic shoes.

Dramatic Finale of 1988 Worlds in Ronse, Belgium

Joe Parkin is a former professional cyclist and the author of “A Dog in a Hat: An American Bike Racer’s Story of Mud, Drugs, Blood, Betrayal, and Beauty in Belgium” and “Come and Gone: A True Story of Blue-Collar Bike Racing in America.”

Photos: Graham Watson, Brancale

Brancale Stories: Phil Anderson June 17 2019

Phil Anderson shares some old stories with Brancale including what it was like being one of the only English-speakers in the professional peloton during the early 1980s, his love of the Tour of Flanders and just missing out on winning the World Cup in 1985 due to illness…

Australian Phil Anderson was a professional cyclist from 1980-1994 and was the first non-European to wear the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. He accumulated more than 90 victories during his career.

What it was like racing in Europe during your early years as one of the only English-speakers and non-Europeans in the professional peloton?

Phil Anderson: “Well, 1980 was my first year as a professional. There were very few English speakers in the professional peloton at that point in time. There was Sean Kelly, but I wouldn’t call Sean Kelly an English speaker because I couldn’t understand a word that he said! There was also Paul Sherwen, Robert Millar, Jacques (Jonathan) Boyer and myself, but we were some of the only English speakers. Steven Roche came in the year after me and then later, Greg LeMond.

It was all different then. English speaking riders weren’t taken too seriously. We were effectively seen as cheap labor. We were strong and we rode our bikes hard for our French team leaders. But then we started winning races. In the 1981 Tour de France, I took the yellow jersey and I was the first non-European to do so.

Then a few years later, all of the American team 7-11 guys came into the picture. Guys like Doug Shapiro, Andy Hampsten, Bob Roll and others. At the same time, there was also a migration of Russians and East Germans into the peloton. They basically had to jump the Wall to get in. Then there were the Colombians too. It was a colorful era with many non-traditional countries beginning to be represented.”

What were some of your favorite races?

“Well, certainly the Tour de France was the most important one. Your livelihood came from good results at the Tour de France. But for me, my favorite races were the Tour of Flanders and Liege-Bastogne-Liege. I never won, but came in second place in each. I had gotten these top 10 results and this made me more and more hungry, but I never was able to get the win.

I won other big one-day events like the Amstel Gold Race and Paris-Tours, but I really wanted Flanders because I lived in Belgium. On the other hand, I never really enjoyed Paris-Roubaix.”

Tell us about one of your best days on the bike.

“One of my best days was the 1984 Grand Prix of Zurich which was in the second half of the season. The course was one huge loop and then three or four smaller finishing laps with a really steep hill called Regensburg Hill, behind the airport. On the finishing laps, there were roundabouts with medians that divided the road in two. With one particular median, each time the peloton would take the same line to one side. A teammate of mine was away in a breakaway and the peloton was chasing him. I was able to jump across the gap up to the breakaway. Then, when we again came to this same median, I decided to take the different line that no one ever took. I jumped over the median strip, powered ahead of the breakaway and ended up winning by 50 meters.”

Link to the 1984 GP Zurich footage.

Tell us about some of your worst moments on the bike.

“In 1985, I was leading the World Cup which meant I was ranked as the best rider in the world. I had had a good year, including winning the Dauphine-Libere and I had finished fifth overall in the Tour de France. Then we were coming to the end of the season to the final race, the Tour of Lombardy. This was the last race before I would win the World Cup in 1985. Sean Kelly was just a few points behind me, so I had to watch Sean carefully during the upcoming race.

But the last week before the race, my health went downhill. I had pain in my hips and shoulders and couldn’t get out of bed in the morning. I spent the whole week at doctors, trying to find out what the problem was but no one knew. I couldn’t train all week but went to the race anyway. Unfortunately, I couldn’t finish the race and had to step off the bike at the feedzone. Sean Kelly ended up winning the World Cup and I ended up number two in the world that year.

The next year the illness continued. It took me several months to find out what was wrong with me and get my health back again. I ended up having a rare type of infection that only hits people with a certain blood type and it became a form of lower back arthritis. It took a long time to diagnose.

Eventually my health came back and the following June I did the Tour of Switzerland and got second place in a stage. Then, later in ‘86 I won Paris-Tours. This felt really good after having been the laughing stock of the press and peloton the whole year.”

What is one of your craziest stories from your racing career?

“So many of the best stories are about what goes on in the race, rather than the results at the end. One of the funniest personal stories I have is about British rider Sean Yates during his first Tour de France. He came up to me on a stage during the first week of the race. We were both on the Peugeot team and were riding along during a sunny day. Poor Sean had gotten sick and had diarrhea. He needed desperately to stop to go to the bathroom. He came up to me in the peloton and said, ‘what can I do about it? I can’t stop, what can I do? Go behind a car?’ I told him he could go in a cycling cap. That it was simple, he could just put it down his shorts and go to the bathroom, I told him that I had heard that you could do that from some of the older, more experienced guys in the peloton. Of course I was joking but he didn’t realize it.

Then I told him that if he wanted to give it a crack, I could give him my cap and that I obviously wouldn’t ask for it back afterwards. Sean was so desperate that he pulled over towards the side of the peloton which was moving at about 50 km per hour. I told him I’d keep my eye on the peloton while he went. This was before bib shorts so he just put the cap down his shorts. It was so funny, he had his hand down his shorts, his face was all contorted and then you saw a huge sigh of relief. Then he pulled out the cap which had a huge gross stain on it and he threw it behind him. The 30 or 40 guys who were directly behind him swerved desperately to avoid the nastiness.”

Tell us what you're up to today.

“Since I retired, I have built a little travel business. We run bike tours at the Tour de France and we also do tours in Australia. Actually, I’m leaving for Budapest soon for a river boat cruise in Europe and then I will deliver 80-100km bike rides every day.”

Note - you can follow Phil at:

Facebook: Phil Anderson

Twitter: Phil Anderson

Instagram: Phil Anderson

www.philanderson.com.au

You had an early endorsement contract with the old Brancale. How did that come about?

“I did a few Giro d’Italias back in the day in the mid-80s with the Panasonic team. I had another sponsor of mine who made an introduction for me to the brand. Then, I secured an endorsement contract for both shoes and helmets. This was an individual endorsement, not through the team. The brand Brancale was the pride of the peloton back then. It was the brand of choice. I even still have an old Brancale leather hairnet helmet lying around somewhere.”

Photos: Graham Watson

"Patent Leather Magic" by Joe Parkin May 07 2019

Former professional cyclist and published author Joe Parkin shares his memories of the iconic Brancale leather hairnet helmet...

It was early fall, 1990, in Dublin, Ireland. I had just finished the final stage of the Tour of Ireland and was collecting myself a little, off away from the crowds and the other riders. I’d gone for the long breakaway — me and Irish rider Martin Early — but our bid had been shut down by one of the other teams. There wasn’t too much time to think about what could have been, though, before I was mobbed by some young boys looking for souvenirs.

They took the race numbers off my back and the bottle I hadn’t tossed away in the finale. I’d already had an Avocet cyclometer stolen earlier in the week, so I was pretty protective of the new one, but they did ask for it. They even asked for my jersey and shoes. I think they would’ve taken my shorts and socks if I’d offered.

And then one of them asked for my helmet.

I only paused for a few seconds. Sure. Why not? As the clock ticked down on the season, the retirement of this particular helmet was inevitable, because the UCI’s new rule requiring pros to wear hardshell helmets was coming. The hairnet was about to become yesterday’s equipment. The straps were salt crusted and the buckle was rusting. In the moment, I wasn’t really feeling all that sentimental.

Thinking about it in today’s terms, why would you be sentimental about a helmet? Unless it was lovingly hand painted for some special event, or perhaps the first of a model that you rode to victory in the Tour de France, it is hard to see feeling much about a helmet. Most modern helmets are over-sculpted devices that are meant to be replaced after every crash and at least once a season. In fact, I find the most recent models to be design atrocities more disgusting than even the first hardshell bicycle helmets.

But that day in Ireland was a different time. In the hairnet days, you bought your own helmet and, in many cases, you kept it for several years. Most were black or white — mostly black — and they went with any team kit in the peloton. And they were optional in several countries, so the teams rarely got involved when it came to helmets.

When I first arrived in Belgium, I was packing a cheap, black, vinyl Cinelli hairnet that had over-pronounced temple-protection straps. Or at least that’s what I thought they were designed for. It was a backup only. Ever since I laid eyes on my first Graham Watson photograph, I knew I had to have one of the shiny, patent-leather models with the Brancale logo. It took a couple bike shop visits and a fair bit of sign language, but I managed to find one — size 58. And when I strapped it on for the very first time in a race, I felt like I had officially arrived. I was a bike racer.

From that first race in Belgium to the fall day in Dublin a few years later, that Brancale hairnet traveled with me to every event. I loved to race without a helmet in France, Spain and Italy, back when you could do that, but the helmet always came with me. With it, I rode the amateur version of Paris-Roubaix in 1987, surviving crashes, flats, broken wheels, rain, mud, cobblestones and my first ride on a velodrome. Helmets were optional for pros in France but I wore it again at the Hell of the North in 1988 on my way to becoming the race’s youngest finisher. And I am wearing it proudly, front and center, as I drag the entire field past the start-finish line, in a Graham Watson photo from the 1988 World Championship in Ronse, Belgium.

That helmet stayed with me through countless crashes and hundreds of Kermis races. It endured beer showers and champagne spray, rain and hail, cow shit, horse shit and pig shit — a lot of pig shit. From time to time I would pick up a Saint Christopher medal and sew it to the square little Brancale logo patch in the front. Other times I would put a Chiquita Banana sticker in the same place. I never started a race without first ensuring that the patent leather and straps had been wiped clean.

To be honest, I knew nothing about Brancale’s history at the time, and I really didn’t care. For me it was that logo and the helmet’s shape and shine. I’d seen it in the magazine pictures I’d looked at before going to Europe to become a real bike racer. The guys in those pictures, they were real bike racers and I wanted to be just like them.

We started the ’91 racing season in hardshells, but sit-down strikes at several races managed to overturn the rule. Perhaps needless to say, I regretted giving away my Brancale. I’m not much for memorabilia, so I really don’t pine to have that old hairnet displayed on a shelf somewhere in my house, but it is fun to see myself in photos from the days when socks were white and helmets seemed mostly to be decoration.

No, you won’t see me riding around anytime soon in a hairnet. Every once in a while, though, when I see or hear stories of all of these broken helmets, I think back to my shiny Brancale: Hundreds of races, and I can’t even begin to remember how many crashes, but it only hit the ground once. One time. Maybe there was magic in it.

Joe Parkin is a former professional cyclist and the author of “A Dog in a Hat: An American Bike Racer’s Story of Mud, Drugs, Blood, Betrayal, and Beauty in Belgium” and “Come and Gone: A True Story of Blue-Collar Bike Racing in America.”

Photo credit: Graham Watson

Brancale Stories: Combination Classification Jersey October 05 2018

Remembering the Combination Classification Jersey at the Tour de France...

It has been a long time since 1989 when the last combination classification jersey was awarded at the Tour de France. First introduced in 1968, the competition was intended to identify the best all-round rider in the Tour by combining the general, mountain and sprint (both intermediate and final) classifications. The best part about it was the multi-colored jersey awarded to the combination classification leader.

The jersey featured random patches of green, red, white and yellow across the top half of the jersey with red polka dots on the bottom half. It was an explosion of color and a patchwork of all of the Tour’s leader jerseys. In short, it was awesome (note: in earlier years it was actually noted by a white jersey but then that later became the best young rider jersey).

Dutchman Steven Rooks of the PDM team has the distinction of being the last rider to win the competition. He repeated in both 1988 and 1989. Before him, French great Jean-Francois Bernard took home the jersey in 1987 when he was touted as the next Bernard Hinault. And before that, American Greg LeMond won the combination classification in both 1985 and 1986, when he also won his first Tour.

Strangely, the jersey has disappeared and reappeared throughout the Tour’s history. It first began in 1968 when Italian rider Franco Bitossi won the competition. The next four years (1969-1972) were dominated by the Cannibal, Eddy Merckx and he again took home the jersey in 1974. Then, for some strange reason 7 years after its introduction, the combination classification jersey disappeared, only to reappear again in 1980. The reappearing jersey was taken that year by Belgian Ludo Peeters. Bernard Hinault dominated the competition in 1981 and 1982.

The disappearing act continued. In 1983 and 1984 there was no multi-colored jersey found among the peloton racing across the roads of France. Clearly, the combination classification and its colorful jersey have come in and out of favor with the Tour organizers over the years.

We think it’s time it was reintroduced. If for any other reason, to be able to see that incredible jersey with its patchwork of color in the peloton again. Alas, this may require some patience as there are no plans to bring back the competition. In the meantime, Brancale has launched a new pair of socks modeled on the combination classification jersey for those nostalgic for the old days.

Brancale Stories: Roy Knickman August 01 2018

Former professional cyclist Roy Knickman shares some stories with Brancale. These include his time on the legendary La Vie Claire and 7-11 teams, his long breakaway in the 1988 Paris-Roubaix and his bronze medal in the 1984 Olympics as a young 19-year old…

Photo: Graham Watson

Roy Knickman was known for having the strength of four men when he was riding tempo on the front of the peloton to control a race. Early in his career he was hailed as “the next LeMond” but Knickman preferred the role of super-domestique and sacrificing himself for his teammates. Even with all this sacrifice, he still won a number of very significant races himself.

What was it like riding on the legendary La Vie Claire team in Europe in the 1980s beside LeMond and Hinault?

Roy Knickman: “It was pretty overwhelming coming into the number one team in the world with Bernard Hinault, a five-time Tour de France winner, and Greg LeMond, the best American rider of the era. But everything in my life at the time was a whirlwind and I didn’t expect any of it. I didn’t expect to make the Olympic team in 1984 as a 19-year old and I didn’t expect two years later to join the best cycling team in the world. I remember showing up at my first winter camp to go skiing in the Alps with Hinault. All I could think was ‘holy crap! This is crazy!’

It was a very European experience. I would go for month long stretches without interacting with a single English speaker. It was a lot for a 20-year old kid. But it was also a huge opportunity and a great experience with many great moments. This was before cycling was ‘work’ for me, rather, it was still a crazy life experience. Later, after 3-4 years it would become ‘work’ for me.

Overall, it was a mix of the traditional and new approach to cycling. Hinault was very much a traditionalist. For example, he washed his own jersey in the sink after each stage of the Tour de France. LeMond, on the other hand, was more from the new school of cycling.

Hinault was very firm as a leader but he was also very giving as a leader. This was evident from his generosity with prize money. All of the prize money went into a communal pot and you got a share at the end of the season based on the number of race days you completed. Everyone got a share, including me. And Hinault never took his share from the pot because he was the leader. His gift to the team was to put his share back into the pot.

Hinault also would ride as a domestique in other races during the season for his teammates. He knew that they would give him 110% during the Tour de France when he needed them so during other parts of the season he would sacrifice for them. He set a good example as a leader.”

You later were on the 7-11 team, what was that like?

“Well, psychologically it was easier than the European school of cycling. It was like coming home. On the 7-11 team, you had a group of guys who spoke English. I was isolated as an English speaker on my French La Vie Claire team. But with 7-11, there was small talk at the dinner table and shared cultural references. I was also able to do a little US racing which was fun too.

Overall, it was easier. The 7-11 model was one where you could have longevity in the sport because you weren’t hating it every day. Management’s goal was to get performance from team members by making the riders more comfortable. It was not about breaking the riders down as it was with the European model, but rather making them comfortable and able to perform their best.”

Can you tell us a little about your early years of racing?

“I began racing in California. My introduction to racing outside of California was a crazy six-week road trip that I took when I was 16 years old. First, we went to SuperWeek in Wisconsin, driving all the way from California. During the trip to Wisconsin, the clutch on my dad’s van broke and we spent the whole time there having to push the van to get it rolling before getting it into gear!

In the first race at SuperWeek, I got dropped but then was able to recover and catch back on. In catching back on, I had momentum and just kept going and somehow won the race. It was my first win of the year and even better, it was against the junior national team members who were also in the race. From Wisconsin, I went on to something called Sports Festival and then later on to road and track nationals.

I then linked up with the Raleigh team and got to ride along in their team van, going to races. It was so cool. I ended the trip by taking a Greyhound bus from Lima, Ohio back to Ventura, California. I had some fat, sweaty dude sitting next to me for three days on the way back home. By the end of the trip, I had raced a giant loop around the country, all as a 16 year-old.

It was this first road trip and my early years as an amateur where I have my most memorable moments and experiences. That first road trip is still by far my most memorable trip. Whether it was traveling across the country by van, staying in host housing, the people we met along the way…those were the days. I try to recreate this with the junior team I am coaching now. I try to instill in them to just enjoy the experience. After all, when you’re 50 years old, who will care what bike races you may have won?”

What were some of your favorite races?

“I liked the smaller stage races like the Tour of Switzerland. I lived in Switzerland so it was sort of a hometown race for me. For me, the grand tours weren’t any fun. They were pressure cookers, the stakes were so high. Every minute of every day was so nervous, with constant positioning among riders in the peloton and crashes. It’s safe to say the Tour de France was my least favorite race, it was too intense.”

What was your best day on the bike?

“My best days on the bike were those where I was able to dig deep and deliver for the team. A good example is the team time trial at the 1984 Olympics. Believe me, it wasn’t because it felt easy. During the Olympic team time trial, the team was in crisis because we lost our core guy due to dehydration. I was five years younger than most of the guys on the team and I was going as hard as I could every pull. Towards the end, there were only two of us who could pull through for the last 10 kilometers. It was the moment where I had to dig the deepest. I was riding with guys I worshipped: Davis Phinney, Ron Kiefel and Andy Weaver. Here I was, the 19-year old kid who came through and helped the team to a bronze medal. I was able to deliver for the team and for these heroes of mine. It was truly a moment of accomplishment for me.

I also had other days on the bike where it went well for me personally. In 1987 I won a stage of the Criterium du Dauphine after a long breakaway. That same year I won a stage of the Tour of Switzerland. Those were big days for me.

But there were also days that were equally satisfying when there was not any significant personal result. Days when I was setting tempo at the front of the peloton to defend a leader’s jersey. I wasn’t a good climber, but if I was able to drive the train for a 20km climb and whittle the field down to just 40 guys for my team leader, it meant I was doing something that was hard for me but I was doing my job well. It wasn’t about the personal result but rather that I was able to deliver for the team.”

What was your worst day on the bike?

“My worst day on the bike was at Paris-Roubaix in 1987. That day, my job was to help my teammate Steve Bauer. It was one of those days with very heavy crosswinds. Early on, the field split up into several echelons. It was like those famous photographs you see where there is an echelon of 15 guys across the road with the last guy at the edge of the gutter, then another echelon of 15 guys and the gutter and several more like that. The field was split into several echelons like this that day. Bauer and I were three echelons back from the leaders. My job was to get Bauer back in the front so I drove at the front of our echelon as hard as I could to get Bauer back to the group in front of us. For half an hour I pushed myself as hard as I had during the ’84 Olympic team time trial to reform the group. I was able to get Bauer up to the second echelon but then I imploded. Afterwards, I couldn’t find any group I could keep up with. By the first feed zone 100km into the race, I couldn’t even ride with the last group.

Afterwards, I was pretty hard on myself, thinking ‘I am a bad bike racer.’ After the race I thought I might even quit the sport. For me the worst part was the psychological aspect of not being able to do the job to support the team. But I was being too hard on myself: it was because I had over-trained that season, I had lost too much weight. Ironically, afterwards I was the only guy who got kudos later during the team meeting after the race. Our director Paul Koechli said, ‘the only guy who did anything today was Roy who was pedaling with only one leg!’”

The following year in 1988, you were in one of the longest breakaways in Paris-Roubaix history, what can you tell us about that?“My role that day was to help my teammates Bob Roll and Dag-Otto Lauritzen. I was young at only 22 years old but it was a day where I had good form, I was strong. I was riding at the front to help my teammates. I was simply covering the early move and ended up in the breakaway of thirteen riders. I wasn’t riding for me, I was riding for Bob and Dag.

Dirk Demol and Thomas Wegmuller were both in the breakaway with me and were incredibly strong. I rode in the top five into every cobbled section with them. Then, coming into the Arenberg Forest, I wanted to be first because I knew it was the worst section of cobblestones. But, I went in too fast and about 500 meters into Arenberg, I tried to bunny hop a missing section of cobblestones. I misjudged it and and didn’t make it, slamming the edge of the missing cobbles and flatting.

Dirk Demol and Thomas Wegmuller were both in the breakaway with me and were incredibly strong. I rode in the top five into every cobbled section with them. Then, coming into the Arenberg Forest, I wanted to be first because I knew it was the worst section of cobblestones. But, I went in too fast and about 500 meters into Arenberg, I tried to bunny hop a missing section of cobblestones. I misjudged it and and didn’t make it, slamming the edge of the missing cobbles and flatting.

This stretch was so narrow and the team cars began to go by me as I tried to find a new wheel. I finally got my wheel replaced but then had to fight to get around the team cars that were blocking the way. I eventually made it out of the Arenberg Forest but was now about a minute down on the leaders. I chased hard for an hour with a few other riders and was able to stay at just about a minute back. Then, the others gave up but I kept chasing alone for another hour until I was caught in the feed zone. I’m convinced that if I hadn’t flatted, I would have finished in the top 10 at Paris Roubaix that year. It was a bummer, but that’s bike racing.”

This stretch was so narrow and the team cars began to go by me as I tried to find a new wheel. I finally got my wheel replaced but then had to fight to get around the team cars that were blocking the way. I eventually made it out of the Arenberg Forest but was now about a minute down on the leaders. I chased hard for an hour with a few other riders and was able to stay at just about a minute back. Then, the others gave up but I kept chasing alone for another hour until I was caught in the feed zone. I’m convinced that if I hadn’t flatted, I would have finished in the top 10 at Paris Roubaix that year. It was a bummer, but that’s bike racing.”

Link to some great CBS coverage of the 1988 Paris-Roubaix with Knickman in the breakaway.

What are you up to today?

“I am a professional firefighter and I am also currently coaching one of the best junior teams in the US. We took what was a small, local team and transformed it into one of the best junior teams in the country. We are based in Southern California and have a great group of guys. It takes a lot of time, hard work and money. I am doing this not simply with the aim to produce future professionals, but to give them an opportunity to have some great experiences at a young age. I think back to my first road trip when I was 16 years old and all of the great experiences I had and that’s what I want for the members of the team. Then, afterwards, I will tell them to get on with life!

Another project I am lining up is the creation of a new under-23 development team. There are at least four great junior teams right now in the US but once these riders become senior-level riders, there are very limited opportunities for them. Therefore, I am aiming to create a new under-23 team and am in the process of raising funds to do so. If any readers are interested in contributing to this team, they can reach me directly at: crk3@aol.com

Brancale Stories: Greg Oravetz July 17 2018

Former professional cyclist Greg Oravetz shares some old stories with Brancale. These include what it was like racing during the 80’s and 90’s, winning the USPRO national championships his rookie season, his view on the evolution of bad cycling hairdos, heavy steel bicycles and the infamous “leather jacket” climber’s jersey at the Tour of Colombia…

Few riders dominated the US racing scene during the 1980’s and 90’s the way Greg Oravetz did. Oravetz was a big, powerful rider weighing 180 pounds with a 6-foot, 3-inch stature. He turned professional in 1989 with the legendary Coors Light cycling team. In his rookie year, he won the CoreStates USPRO national championships and the resulting stars and stripes jersey. To this day, he is still the youngest rider to have won the race.

Brancale asked him to share some stories from his years as a professional cyclist.

Tell us a little bit about what the racing scene was like in the US back in the 80’s and 90’s compared with now.

Greg Oravetz: “The 1980's were so different from the 1990's. I personally started getting serious with cycling in the early 80's. I went to a training camp run by Greg LeMond. The camp changed everything for me. It was a tipping point where I realized one day I could be a professional.

In the 80's, equipment was rarely the deciding factor in races. Bicycles were so low tech that it was a level playing field. It was also around this time when cycling apparel began to evolve. Cycling shorts went from being wool with a natural chamois to being Lycra with a synthetic chamois. Back then, we really thought that was a break through!

When the 90's rolled around, the the bad hairdos started and equipment became a lot more important. At the time, my bikes still weighed 22 pounds. As they say, ‘steel is real.’ Real heavy and real flexible.

Throughout the 90’s, they kept adding gears to the bikes and moved the shifting from the down tube to the handlebars. The hardshell helmet became mandatory and the leather hairnet vaporized. Day-Glo was white hot!

Guess what? Day-Glo is back. Bad hairdos and white shoe laces are all back. It is all new again because people forget why they stopped doing it in the first place."

What were some of your favorite races?

“My favorite race was Paris-Roubaix by miles. I raced it two times as an amateur. To my great regret, I never had the opportunity to make it to the starting line as a professional even though I believe it was the best race for me. I loved the classics. The wind, narrow roads and the pave defined the day. You needed a lot of luck to get through these races.”

You spent some time early in your career racing in France for an amateur team, how was that as an American?

“Racing in Europe was the best experience ever. I was able to see how my body coped to racing 100+ mile races every week and I realized how much more it suited my talents. Riding around in circles was never something I liked, but that is mostly what you have in America. When I was in France racing, Greg LeMond was the prince and so being an American gave me a chance to test myself.”

You won the USPRO Championships in Philadelphia in your rookie season, what was that like?

“1989 was a big year for my career as a cyclist. I was now a teammate of LeMond and Alexi Grewal who I saw win the ‘84 Olympic gold medal in my backyard in California. Coors Light was the top domestic-based team in America. The Tour de Trump (later the Tour Dupont) and the USPRO Championships in Philly were the biggest races that year. After a very disappointing Tour de Trump where I fell ill and had to abandon, I trained really hard for Philly. As an underdog, I had a huge advantage. Even though I had been one of the top amateurs in France in 1988, I was almost completely unknown in the US. During the race in Philadelphia, everyone watched LeMond and Alexi Grewal [ed. LeMond had flown in on the Concorde for the day to race in Philadelphia before going on to win the Tour de France the following month by 8 seconds]. I made it into the key break away of the race along with Ron Kiefel and Mike Engleman. In the end, my training payed off and I was able to finish off what I had dreamed of all summer. I am still the youngest winner of that race.”

Do you have any crazy stories you can share with us?

“A crazy story? I could write a book on crazy stories! One funny one is from the Tour of Colombia, back in I believe 1991. The team needed a good training block in warm weather and the altitude of Columbia was a bonus. The race was pure insanity in terms of safety, the fans and the hot weather. We were just beginning our season and did not really have the same fitness level as the locals. But when the opportunity for a victory is there why not try? The first stage was an individual time trial and we had Steve Swart who was an amazing time trialist.

Swart was nearly last to go on the day and he just cooked it, finishing a good margin ahead of the next rider. With only a few guys left–none of whom had any real chance of beating Swart–it was time for him to clean up and get ready for a podium appearance to put on his new tour leader jersey. Then as we stood on our balcony watching the last rider go blasting by, to our amazement this rider who was one of the world’s most famous climbers beat Swart by almost 20 seconds! How? Simple, he sat on the bumper of not one, but a paceline of three motorcycles going 35mph! That was just the beginning though.

The next stage was a flat one and we wanted to show that we were not just there for a sun tan. As we approached the finale, I was part of the lead out train and the second-to-last taking my turn at the front before our sprinter would raise his arms in victory. Only it was one banner too soon and he looked up to see yet another banner and had to keep going. Luck was not on our side!

The weather was in the upper 90's most days and the king of the mountain (KOM) jersey was black. Yes, not all climbers get a polka dot jersey. We dubbed it the ‘leather jacket.’ The black climber’s jersey was a death sentence to every rider who put it on. The team decided not to try for the KOM jersey because of all the great local climbers. It was such an important jersey for these locals who were dying to get it–and then really dying once they got it!

Oh, let's not forget the huge crowds and stray dogs. It is great to race where people have passion and the crowds are big. At the same time, many times we would roll into a large town thinking it was going to be a good sprint but then a wild dog would run into the field, crashing the unlucky. I closed my eyes on more than one occasion!

What opened my eyes were the awe-inspiring climbs and those who lined the mountain roads to cheer for the brave. One stage I was feeling good and managed to be in the top 20 on a big climb. Some kids were along the side of the road asking to push us and others were on BMX bikes, giving us a run for our money up the climb. When they would finally tire, they would reach over and swipe the water bottle right off our bikes. It was an amazing and hilarious experience.”

Tell us about your best day on the bike.

“My best day on the bike was my first classic win at Paris-Marquenterre in 1987, as an amateur. It was a race that finished up near the northern coast of France. My legs were so good that day that I could simply ride in whatever gear I felt like. When I finally decided to attack, it seemed effortless, almost like I just ‘fell’ off the front. The weather was perfect–in the high 70's–and in the final 10 kilometers I pulled over a minute ahead of my final breakaway companions to win solo. My sponsor was so proud, it was a beautiful moment.”

Tell us about your worst day on the bike.

“My worst day on the bike would have been at the Tour of West Virginia in the early 90s. It was raining and about 38 degrees outside. Our team had missed the move and I got put on the front to chase for about 60 miles. We did not have much help from other teams and I really wanted to abandon and climb into the warmth of the team car. My legs felt totally flat but somehow I found the reserves to keep fighting for my team. The effort felt like I took a 100-mile pull into a headwind while someone was holding onto my seat. On top of that, my hands and feet were frozen.”

What are you up to today?

“I still work in the cycling industry today. I have been an outside sales rep for Cannondale, Cervelo and Speedplay. Now I work with Belmont Wheelworks, a premier bicycle retailer and with Gerrard Cycles. On the side I am also still involved with cycling camps. A year ago I worked a camp for Ryder Hesjedal which was a lot of fun.”